Brandon Sanderson is widely respected as a meticulous world builder, an innovative storyteller, and a prolific writer. Over the past two decades he’s made his name as a crafter of ultra-refined magic systems and dynamic characters.

But no methodology is flawless, and new writers can learn just as much from examining how Sanderson’s style falters as they can from his successes.

“Wait,” I can hear some of you saying. “Isn’t Sanderson the guy you’ve held up as a model of Neopatronage? Hasn’t his writing raked in tens of millions of dollars? How can you say it has flaws?”

And the answers are: Yes, yes, and nothing manmade is perfect. Professional authors are always working to improve our writing, so suggesting areas that may need strengthening does us a service.

That being the case, what is Sanderson’s Achilles’ heel? In short: constantly dynamic characters.

Hat tip to @MichaelFKane on X for his insightful initial analysis.

One of Sanderson’s strengths lies in crafting dynamic characters: individuals who undergo significant growth and change over the course of a story. But virtue taken to excess can become a vice.

In The Way of Kings, for instance, Kaladin’s arc presents us with a powerful and complete transformation. He begins as a broken slave and rises to become a leader and hero. However, as Kane observed, Sanderson’s tendency to keep his characters dynamic across thousands of pages begins to wear thin.

Dynamic characters can make for good storytelling, but they’re not meant to be perpetual motion machines. A character cannot endlessly undergo life-changing revelations without diminishing returns. For long series like The Stormlight Archive, the continued reinvention of a character like Kaladin—who faces new personal crises in each installment—starts to feel repetitive. Take Kaladin’s PTSD arc. While realistic, Kane notes that it no longer feels natural.

Related: Why Not Every Fantasy Story Needs a Magic System

By the way, I’m not just picking on Sanderson. Many successful authors, especially those of Generation Y, fall into the constantly dynamic character trap. The problem is that characters who undergo too much development can begin to feel unanchored, as if they lack core identities.

A major error beaten into Sanderson’s generation dictates that flat or archetypal characters are de facto poorly written. But that’s not necessarily the case. Characters who remain fundamentally the same throughout a story needn’t be lifeless or boring. Flat characters can still be compelling because they represent ideals, forces of nature, or stable moral anchors in a chaotic world.

And characters who maintain their equilibrium over time can be stable, consistent points of contact which help get readers attached to a story. Using archetypal characters frees authors to focus on fresh conflicts and themes without needing to reinvent their protagonists.

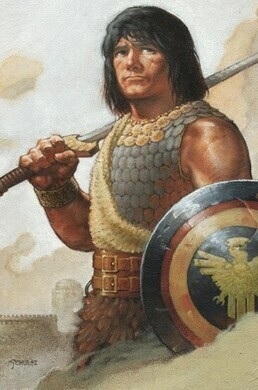

Take Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Cimmerian. Conan does not undergo dramatic changes in personality or worldview. He remains a larger-than-life hero: strong, confident, and determined. His consistency allows readers to focus on the ever-changing obstacles he faces.

Similarly, in Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, characters like Aragorn and Gandalf remain steady and unshaken in their principles. They are not static in the sense of being uninteresting; rather, they act as pillars of stability amid the story’s upheavals and uncertainty.

Related: Sanderson v Tolkien, Magic v Sacrament

Flat characters can be especially useful in epic or mythic tales which deal with grander themes. Instead of staying laser focused on individual psychology, authors can use archetypal characters to explore the war between good and evil, the triumph of heroism, or the power of destiny.

Many modern works have stripped such archetypes of their transcendent power. Dragons, once symbols of chaos and primal evil, are often reduced to fire-breathing lizards (Looking at you, Patrick Rothfuss). In contrast, Tolkien’s elves remain timeless because they reflect his belief in the sacred and eternal. By prioritizing symbol over technical detail, authors can imbue flat characters with deeper meaning. Instead of placeholders or mirrors; such archetypal characters act as windows into higher truths about humanity, morality, and the cosmos.

Related: Why Materialism Holds Back the Right’s Next Great Storytellers

Another lesson writers can learn from Sanderson’s struggles with character arcs is the importance of letting a character’s development reach its natural conclusion. While it’s tempting to keep pushing a character through new revelations, there comes a point at which every arc should resolve so the character can settle into the new, hard-won status quo.

That’s not to say the character becomes irrelevant. A resolved character can continue to play a central role in the story without needing constant reinvention. Going back to Aragorn, he completes his arc by accepting his role as king and fulfilling his destiny (which the Jackson films needlessly delay with their formulaic adherence to Refusing the Call, but that’s another post). Once Aragorn claims his destined role, he remains a strong presence without requiring further internal crises.

Remember: Effective storytelling arises not from endless development, but from building stories on a foundation of belief. Tolkien’s convictions gave his characters weight. When character arcs resolve naturally, they allow room for symbols and themes to take center stage.

When planning long series, authors should pace their characters’ development carefully. Not every book needs to put a protagonist through a life-changing ordeal. Sometimes, letting him maintain his core identity while navigating external challenges is the best way to keep reader interest and build to a satisfying conclusion.

While Brandon Sanderson’s dynamic characters are a key strength of his storytelling, they’re also his biggest pitfall. Constant reinvention can become exhausting and unsustainable over time. That’s not to argue that you should only write flat characters. It is to advise that when writing dynamic characters, keep the following tips in mind …

Dynamic characters need room to breathe. After a major arc, let your characters rest in a stable state before introducing new personal trials and tribulations. Arcs that introduced positive change are no exception: Give your characters time to celebrate big wins.

Balancing dynamic and archetypal characters can supercharge your story. Archetypes can serve as foils, moral anchors, or aspirational paragons for your dynamic characters to play off of.

Prioritize meaning over detail. Overexplaining backstories or magic systems risks stripping characters of their symbolic power. Use archetypes to convey deeper truths without too much exposition. Stained glass windows don’t have subtitles.

Let arcs resolve naturally. Forcing constant transformation risks undermining a character’s established growth. A character who has completed his arc can still contribute to the story.

Brandon Sanderson’s work demonstrates the power and the limitations of dynamic characters. By balancing dynamic growth with archetypal stability and knowing when to let arcs conclude, authors can weave tales with emotional weight and lasting appeal, whether they span 300 pages or 3,000.

Get early access to my works in progress, the chance to influence my books, and a VIP invite to my exclusive Discord.

Sign up at Patreon or SubscribeStar now.

Dark fantasy minus the grim plus heroes you can root for battling overwhelming odds–at a Christmas discount.

These are all great points. Sanderson’s problem is that he tends to make almost *all* of his major characters dynamic, and at least for me, this tends to lead to fatigue when reading something like the Stormlight books.

How well perpetual dynamism works is also really contingent on what sort of person the character is. If we’re talking about a thief, or a jester, to give a few examples, constant change and reinvention feels natural because a clever, risk-embracing character is probably going to encounter more of these kinds of perpetual conflicts due to their core personality and tendencies. As a writer, you don’t have to work all that hard to keep the character dynamic.

But as you point out, with someone like Kaladin who seems like he should be an archetypal heroic character, it can feel like contrived or overwhelming situations or internal conflicts are necessitated by the plot in order to keep the dynamism train moving.

It seems like ideally, your story should have a mix of both types of characters, probably restricting constant change to only a couple of characters, at most. That could be the primary protagonist, but it certainly seems like having those archetypal characters around to balance things out leads to stability in the story. This is just what we see with LOTR, where Frodo’s change and conflict is balanced out by Gandalf and Aragorn, and even Sam. The story would be exhausting if all of them were dealing with a personal crisis all the time.

Yes, the dynamic-archetypal mix is the sweet spot.

Solomon Kane strikes me as a great example of a “flat” character that nevertheless is fascinating to read about. Almost everything you need to know about is given to you in the first couple of pages of Red Shadows: Solomon Kane is a man who will travel halfway around the world to avenge the death of a girl that he never met until moments before she died. Howard does add hints of depth to the character throughout his stories, but for the most part he always remains an unyielding and brutal champion for the weak and the oppressed, wherever they may be.

There is a movie adaptation of Solomon Kane and of course the writers felt the need to explain to us how Solomon Kane got like this and what his personal stake in his crusade was. And this made the character boring and generic.

The way I describe Solomon Kane to people who hadn’t yet heard of him is “A post-Renaissance D&D paladin who messed up and lost his priest spells but takes heads anyway.”

Murder mysteries are a genre that depend on undynamic/no story arc but interesting characters. The detective hero needs to be full actualized* before we begin the adventure with them. They are the moral compass of the whole story. They can’t decide in the middle of the investigation to take some side quest to discover the nature of truth. They have to be the hero from the start without some character change.

The characters involved with the mystery can have arcs, but the whole genre necessarily encourages one time arcs that are not necessarily the focus of the story.

*Yeah, blech. It was just the word that came to mind

That’s a good point.

I kinda feel like a bit of a point was missed here. Like… you beat around the bush, went around it in a circle, pointed to some other bushes, identified that bushes exist, and then failed to actually notice that this is, in fact, a bush.

The issue isn’t that having dynamic, or even continually dynamic characters is a problem. Because it’s not. The issue is you have finished the character’s story arc.

Why does it work to have a fairly static character like say… Superman? Because the point of the story isn’t about Superman. It’s about the things that happen around Superman. Same goes for Conan. They’re essentially the equivalent of playing “the straight man” to the world’s absurdity around them, despite being powerful. You’re not doing a character study on them, you’re using them as a focal point for the action.

A highly dynamic character is fine! It’s good, even! If something major happens to a character, yeah, they should change to some degree based on what happens to them. The thing is though, once that major story arc has resolved… you’re done with it. You could add a new story arc for new changes, but the problem is that this should be done with a new character. If you keep doing it to the same character over and over, it’s generally a bad thing.

There are obviously exceptions to this. For example, if you’re specifically and explicitly trying to do something like watch the gradual decent into madness such as in the first Joker movie, where it’s one bad thing after another so you can watch them not just snap, but progressively keep breaking over and over to see what can drive someone to the depths of despair and going beyond redemption, it’s fine. That was like the opposite of a redemption arc, where the whole point was to see what could take a fairly nice guy who tried to be good, and change his nature to the point he was so cynical and hateful he’d kill in cold blood just because he felt like it would make a point.

The reason why it works there though, is that the entire story is focused on a longer story arc of watching the character keep changing progressively for the worse across multiple events. It works because they knew that from the start and had that goal in mind, and it’s built with that understanding throughout. It’s not just random, arbitrary events that just keep happening to the same guy, it’s specifically supposed to be a fall from grace situation via a death by a thousand cuts methodology. Not a single one of those events could have broken him so completely, it took a lot of them compounding in a row to have that effect.

So to digress to my main point, it’s that even the Joker movie was a single overarching story arc. And when it was finished… it was over. You need a different story now. The story can’t be about the same thing, where you keep changing him over and over again, because you already did that. There’s no real room for a redemption arc or anything because that’s the same thing all over again, just in a different direction. Yeah, it’s somewhat different, but it’s too much of the same thing. You do that to a different character instead.

A character study story is about studying the nature of a character. What makes them who they are, why they are the way they are, how they change and grow and so on, and these are perfectly good stories. It’s just once you’ve finished that story, it doesn’t really work to tell the same story with the same character a second time, because you’ve already studied that character.

You can tell other story types with the same character, such as the Conan example, because the focus of those stories aren’t on studying the nature of the character, it’s about this evil cult, or a monster, or some demon. You can have the same character interact with these things just fine each time because the audience isn’t really concerned with the character at the center of it, because that’s not the focal point of the story and why the story exists. Conan’s story arc and character study is in his being raised as a slave, becoming a man as a gladiator, and that sets who he is. You do that story arc ONCE. After it’s done, you don’t go back to it. You don’t do the same story twice. We’ve already done that story. So Conan doesn’t really change a whole bunch in later books and movies, because we’ve already done the story exploring his dynamic evolution as a character. If you want to explore the dynamic evolution of another character in the Conan universe, you can! It’d be fine! But you can’t do a character study on Conan himself a second time. Or a third. Or a fourth.

So… can you break this? Again, yeah, you can break any rule, but you have to know why the rule exists. To break this rule, we have to understand that the purpose of character development in large ways is to explore what changes the nature of the character. That is a story that can really only be told once. …But you can tell the story about the same character changing in different ways if the purpose of the story isn’t to explore the character themselves, but rather to explore the nature of change itself.

As an example of this, Planescape: Torment is a game which is on pretty much every “top 10 video games of all time” list for a very good reason, not just despite that the story is explicitly about a perpetually dynamic character, but specifically because of it. The story isn’t about the nature of the character, but about the nature of the nature of what makes a character change at all.

The story in this game famously asks, “What can change the nature of a man?” Well, let’s make this guy immortal, wipe his memories when he dies, and see if he winds up being the same guy each time he revives. Now we get to see several different incarnations of the same character, multiple versions where sometimes he’s a hero, sometimes he’s a villain, sometimes he’s completely paranoid and neurotic and knows future versions of himself will try to ruin things he has accomplished.

It’s not a character study, though. It looks like it on the surface, but it’s not studying the one character. Rather, it’s studying the nature of a character study itself on a meta-analysis level. By its very nature, it requires that you be able to perform the same character study multiple times on the same character.

As a game, it also has extremely high replay value because you can play that character in a wildly different way each time. It’s still the same starting point, it’s still the same character, but how things change each time actually is playing into the larger aspect of the meta-analysis, which is the point of the story of the game, rather than the analysis itself.

So can you have a constantly dynamic character? Absolutely. But you either need to only study their nature of constant change once (story arc finished), or you have to have the nature of the story be based explicitly around the fact that they’re constantly changing (meta-analysis of the nature of character studies is one of the few good ways to do this) for it to work.

As such, a constantly dynamic character is fine to explore the one time, but once you have explored the concept of such, you’re done, you can’t really keep doing it and having that be the nature of the story. That’s where it fails. It’s why Garibaldi’s two story arcs of crawling back into the bottle on Babylon 5 didn’t work, because they’d already done that story arc and completed it. Yeah, the second time was better done and more in-depth, but we’d already covered that ground and it didn’t need to be repeated.

Even having a constantly dynamic character as a background thing that’s going on can work, but it can’t be the focal point of the story every time. It can be a strange side character who seems totally different each time they show up, and that’s part of what makes them so odd and distinctive, but it’s a side character, it goes away after a glimpse into their current state. You can keep coming back to it as a recurring joke for example, and it can even become better by stretching the joke out to obscene degrees over several books, but it can’t be the focal point of the story because the story isn’t actually progressing.

Which is the real reason it doesn’t work. Yeah, I wandered around too, I’m guilty of not just beating around the bush, but wearing a pretty good trench down around it. Could probably fill it with water and make a moat out of it at this point, but whatever. So my last little bit will just snipe the bush now that we’re done scaring it with saturation artillery strikes in a circle around it, because you’ve put up with reading this far already, may as well reward you, right?

The real truth is that the story arc of “character experiences something that changes their worldview!” is an arc. It has a start, and it has an end. That’s the nature of an arc. It’s kinda definitional, even. If they’re constantly changing, perpetually dynamic, then that arc never finishes. It never even progresses because you never get something new, and it never finishes nor moves closer to finishing. The specific details may change, like oh the character has PTSD now, as one of your examples had been, but the story arc of “the character changes” hasn’t actually changed any. The character changed. But that’s what they always do. They did the same thing they always have. We’re not any closer to the “final version” of the character. There’s an infinite number of points between where we started from and where the end is, and we can just cram more points of change in between those two and it doesn’t increase or decrease our position any, we’re just trapped in an infinite, endless series of changes to the character with the story arc stretching off infinitely into the distance, never reachable, never obtainable. We move halfway there, then halfway again, halfway again, but it never reaches the end. The end is still out of sight, not just out of reach, but perpetually so far away we can’t even imagine seeing the end.

This isn’t a story arc, then. Because there is no end to it. Do we have a name for that? Sure we do! It’s called “bad writing.” Or being abusive towards your audience. Kind of significant overlap, really. Making a promise (a story arc has an end!) and never delivering on that promise (there is no end, it’s not actually a story arc, lawl) but dangling the hint that you’ll someday actually deliver on the promise when you really have no intent on ever doing so.

So to avoid that, I shall stop here. I will deliver my promise of fulfilling the end of this story arc which has been affectionately named at this point “Dear gawd, why won’t you shut up?”

At least until the 37th installment. I never said I was a good writer. I never said I wasn’t evil, either. Deal with it. Mwahehee.